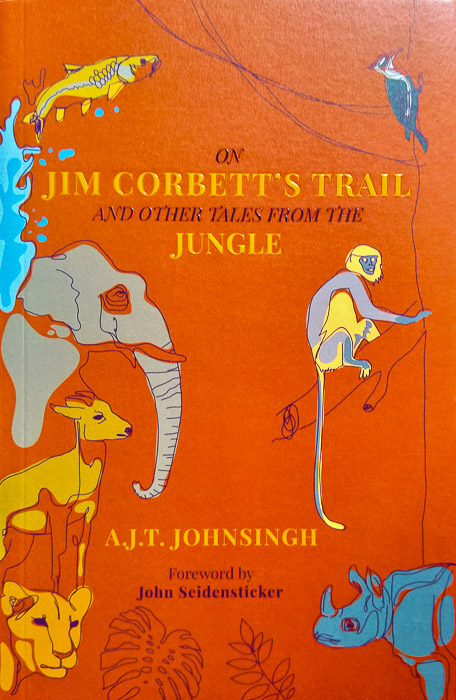

On Jim Corbett’s Trail and Other Tales From the Jungle

by A.J.T. Johnsingh

Jim Corbett. The name evokes so much of awe, reverence and inspiration in many of us. His books have got millions of people hooked to wildlife in India and abroad. I was also one of them and the author of “On Jim Corbett’s Trail and other tales from the jungle” Shri A.J.T. Johnsingh being one of the more celebrated ones. He is author of some lovely books depicting his work and experiences like “Field Days”, “Walking in the western Ghats” and a two volume tome called “Mammals of South Asia” which he coedited with Neema Manjrekar. It is no wonder that when I heard about the book I became really eager to read it.

The first part of the book is focused on the author A.J.T. Johnsingh trying to visit all the places mentioned in the books of Jim Corbett. Over several attempts, the author along with some of his colleagues have tried to cover all the small villages mentioned by Jim Corbett when he was moving in search of the maneaters.

Most of those places remain etched in the memory of fans of Jim Corbett books even though many have never got an opportunity to set their feet in those remote places. The author found that it takes a combination of travel by jeep as well as several days of walk by able bodied men to reach some of those places where Jim Corbett roamed around without any assistants and often without food. That a man can undertake such hardships not for pleasure but to complete the unpleasant task of killing a maneating tiger or leopard, when at any step the hunter can be hunted, tells us a lot about the mental strength as well as selfless spirit of the legendary Jim Corbett who never accepted any reward for killing the maneaters.

Since Jim Corbett was a phenomenal naturalist and has given vivid descriptions of the flora and fauna of the places where he was hunting the maneaters without which the biodiversity of those places would have remained unknown. Johnsingh has documented the present day situation of wilderness and wildlife in those remote regions of Uttarakhand and Corbett’s writings serve as a benchmark to compare the decline of wildlife in the roughly 7 or 8 decades.

India is plagued with overpopulation with our population exceeding 1.3 billion. So our wilderness areas are under tremendous pressure. Wildlife is vanishing at an alarming rate due to rapid concretisation of the places. So when Johnsingh spots deserted villages he also spots an opportunity to create tiger reserves and accord protection to the areas so that there is a realistic chance of sambar and other herbivores bouncing back in numbers and ensuring that tigers can have a sufficient prey base.

Johnsingh has mentioned the example of protection of Serow in Japan where it was designated as ‘natural monument’ and later in 1955 upgraded to ‘special natural monument’. With large scale afforestation cum habitat improvement and protection of the species, the Serow population “shot up from 75,000 in 1980 to 100,000 in 1985.”

With increased human population the anthropogenic pressures has increased and the wildlife is bearing the brunt of it. Relocating the villages will be of great help. Johnsingh also found that there are some villages who are demanding to be moved out of the forest. “The Teria village has a population of about forty families… complained that crop raiding by sambar and wild pigs was a serious problem and that they would happily move out of the jungle provided they are provided a suitable resettlement package.” He also suggests that one option can be to allow the villages to suffer natural decay as the young ones move out to the cities in search of jobs and a modern lifestyle.

The author suggests special management inputs for Corbett Tiger Reserve “which has the only viable population of tigers in the entire range, would need special management inputs to enhance prey abundance. The southern boundary plantation forests of the Reserve, with monoculture plantations of teak and eucalyptus, 350 sq. km are adjacent to the plantations of the Bijnor Forest Division. Two hundred to three hundred firewood cutters, who come on bicycles every day and take firewood for sale to far-off places, disturb the area. Wood cutters can take away fresh kills also…. The monoculture plantations, particularly teak, when compared with the surrounding vegetation are inferior habitats for sambar and pigs, as they do not offer the cool shade critically needed in summer. Besides, teak plantations do not offer enough cover (from December to June) to the tiger, which is a stalking predator, to hunt successfully. Therefore the prey (cheetal and nilgai) that are found in the plantations remain largely unavailable to the tiger.” These inputs are also relevant for other forests.

During his treks along the Nandhour river valley the author describes his encounters with poachers clad in camouflage clothing and having guns, spears and dogs. In one such encounter the poachers ran away while open firing in the air when they saw that they are being photographed. Johnsingh has estimated that the Nandhour landscape has the potential to sustain 30 tigers and had called for creation of Nandhour Tiger Reserve. Creation of a Tiger Reserve and completely stopping poaching can only help increase the preybase and the tiger numbers. He suggests dedicated field manager for the area is fit and treks a lot as the impact is better if the effort is top down. That will motivate the subordinates to move into the field. Along with that he has suggested recruitment of ex-army personnel as well as persuading the elders in the village of the poachers to give up poaching.

The author notes the impact of deforestation and habitat degradation on the lives of people. “In the past, most villages in the lower reaches of the outer Himalaya had two settlement locations, one for winter and the other for summer, three to five kilometres from the winter settlement up in the hills. The summer settlement was always situated near a perennial source of water. In the beginning of April, most of the populace with their livestock moved to the summer settlement…the migration was largely because of livestock. The Kanda village was abandoned in the early 1970s, when its inhabitants started living permanently in Kanda nallah, their winter settlement, on the right bank of the Mandal River. Similar abandonment of summer villages has happened in many places in the Himalaya; one major reason for this is the drying up of the water sources due to habitat degradation, caused by excessive lopping, unregulated fires and grazing.”

It is a sad that that these kinds of impact of humans on wilderness areas and the resulting area becoming unliveable should have been documented and used to educate the masses as well as the policy makers much earlier. The causes of rural to urban migration of people being caused majorly by human induced habitat destruction and climate change should be studied in more detail to help the policy makers.

Like Jim Corbett, Johnsingh too is fond of Mahseer, a group of freshwater fish, which can reportedly grow to weights exceeding 100kg with 50-70 kg specimens routinely caught in the past by anglers, are. Unfortunately such large Mahseer are no longer found. In the chapter ‘The Flight of the Mahseer’ the author talks about the problems faced by Mahseer leading to its virtual decimation in many parts of its former range. “The decline has been due to a combination of factors including the use of electricity and poisoning, which destroys brood fish and juveniles. Pollution, the silting of rivers and the construction of dams have impeded migration, which is crucial for spawning. But the most lethal is the use of dynamite, easily available from organisations such as the Public Works Department and the Border Roads Organisation. Dynamite kills adults, young fish and even the developing larvae. Dynamiting has decimated mahseer populations in most parts of its range.” It is important that people realise that they need to take steps to save the Mahseer. “People need to be convinced that fish is a renewable resource, but it cannot renew itself when it is being massacred thoughtlessly. Spawning sites need to be protected; the rivers should be kept clean. More youth should be encouraged to take up angling and fishing must be regulated.”

In the second part of the book, Johnsingh has looked at other wilderness areas in South, West, Central India as well as East and North East. One can find a similar approach of solving conservation issues of the species residing in those areas. So when in Kalakad Mundanthurai he is talking about stopping poaching and relocating Tahr from the 9th hairpin bend in Pollachi-Valparai road to Kottangathatti and Kannunni peaks; in Gir he is espousing the lost art of lion-tracking to help keep the staff fit as well as help in conservation and in Mishmi Hills he is asking for banning .22 air rifles.

There are also many interesting information about natural history in the book. In the chapter on leopards Johnsingh writes an incident where the leopard is using the tip of its tail to attract attention of the deers to make them come closer to investigate brining them into the ambush range. In the chapter titled “The Lure of The Langurs” he writes about the feeding association of cheetals with langurs. “Being wasteful feeders, the monkeys were dropping lots of plant parts and to my pleasant surprise I found goral, cheetal, barking deer and sambar feeding on the plant parts dropped by the langur….Paul Newton following one group of langur in the sal-mixed forest, oveserved that “the group dropped nearly fifteen hundred kilogrammes of food in a year. The dropped forage was eaten by cheetal, both in summer and in winter…making a beeline, sometime from as far as two hundred meters away, for the trees where the langurs fed. Cheetals are main beneficiaries of this association – they not only get food, but are also warned of predators by langur alarm calls.”

Perhaps realising that our generation has more often than not failed in the battles to save Wild India from being destroyed and dismembered, the author seems to repose his hope on the younger generation and ends his book with a chapter titled “How I became a Man-eater”. Kids will obviously love this chapter and hopefully love for the wild will be germinated in their tender minds.

One man’s love for Jim Corbett can actually result in creation of wildlife sanctuaries, national parks and tiger reserves. If only the Government listens!

Johnsingh has done a fantastic job of documenting the problems in areas where Jim Corbett had moved around as well as in other parts of India and he has also identified the opportunities for saving these beautify and fragile ecosystems. It is now up to us the readers of the book as well as conservationists and activists to put pressure on the Government to bring his suggestions to fruition.

The book “On Jim Corbett’s Trail and other tales from the jungle” is published by Natraj Publishers and has 258 pages. There are many colour photos as well as black and white photos maps and a few sketches. The black and white sketches evokes nostalgia as they will remind people about Jim Corbett’s books. The book comes with extensive references as well as Scientific and English names of all vertebrates. The botanical names of plants have been weaved with the narration in the chapters itself and will be of help to budding naturalists as well as to researchers and others to identify the species and know their impact. The book is priced at Rs. 595/– and will appeal to naturalists, conservationists, researchers as well as students and laymam. It is a must buy for your home library as well as for gifting to friends and kids.

Highly Recommended!

- Endangered Wild Buffalo of Kaziranga - 4 July,2024

- Leopards: The Last Stand Trailer 2 - 1 July,2024

- GoPro Hero 12 Black - 6 September,2023